The Food Guide Pyramid was a recognizable nutrition tool that was introduced by the USDA in 1992. It was shaped like a pyramid to suggest that a person should eat more foods from the bottom of the pyramid and fewer foods and beverages from the top of the pyramid.

The Food Guide Pyramid displayed proportionality and variety in each of five groups of foods and beverages, which ascended in horizontal layers starting from the base and moving upward toward the tip: breads, cereals, pasta and rice; fruits and vegetables; dairy products; eggs, fish, legumes, meat and poultry; plus alcohol, fats and sugars.

In a nutshell, the Food Pyramid is a visual representation (structured in a pyramid form) that illustrates how different foods and drinks contribute to a balanced diet, and impact one’s overall lifestyle. Many remember this diagram being shown to them in school, usually in P.E or health class. Since 1992, the Food Pyramid has been a cornerstone reference for a well-balanced diet, one that many have been encouraged to tailor to their own lives.

While there are many stances on the Food Pyramid’s validity, a staple argument is the pyramid’s recommended serving size for grains and carbohydrates. While both are essential for a healthy lifestyle, critics began finding clear correlations between obesity and the recommended serving of carbohydrates roughly 15-20 years after 1992. While the USDA ultimately replaced the Food Pyramid with a more proportionally accurate model in 2011, the shape remained the same.

The previous Food Pyramid model places a heavy importance on refined grains including pastas, potatoes, breadsticks, and cereals, stating that Americans should consume 4 servings per day. The problem with this is that the Food Pyramid does not encourage wholesome grains that are full of nutrients and fiber. Instead, it leads Americans to believe that starchy, calorie dense (as opposed to nutrient dense) grains should be consumed more than any other food group.

The first food pyramid

The development of the USDA Food Guide Pyramid spans over six decades. The first National Nutrition Conference, prompted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was held in 1941. As a result of this conference, the USDA developed Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) and specified caloric intakes and essential nutrients. In 1943, the USDA announced the ‘Basic Seven’ which was a special modification of the nutritional guidelines to alleviate the shortage of food supplies during the Second World War. The seven categories included milk, vegetables, fruit, eggs, all meat, cheese, fish, and poultry, cereal and bread, and butter. To simplify, the ‘Basic Four’ was introduced in 1956 and continued until 1979; categories included milk, vegetable and fruit, meat, and grain. With the rise of chronic diseases, the USDA addressed the roles of unhealthy foods and added a fifth group in the late 1970s: fats, sweets, and alcoholic beverages to be consumed in moderation.

A dramatic shift occurred with the 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, which transitioned from the circular image to a pyramid. The pyramid shape was intended to visually illustrate the amounts of each food group that should be consumed from the wide base (cereals and grains) to the narrow top (fats, oils, and sweets).

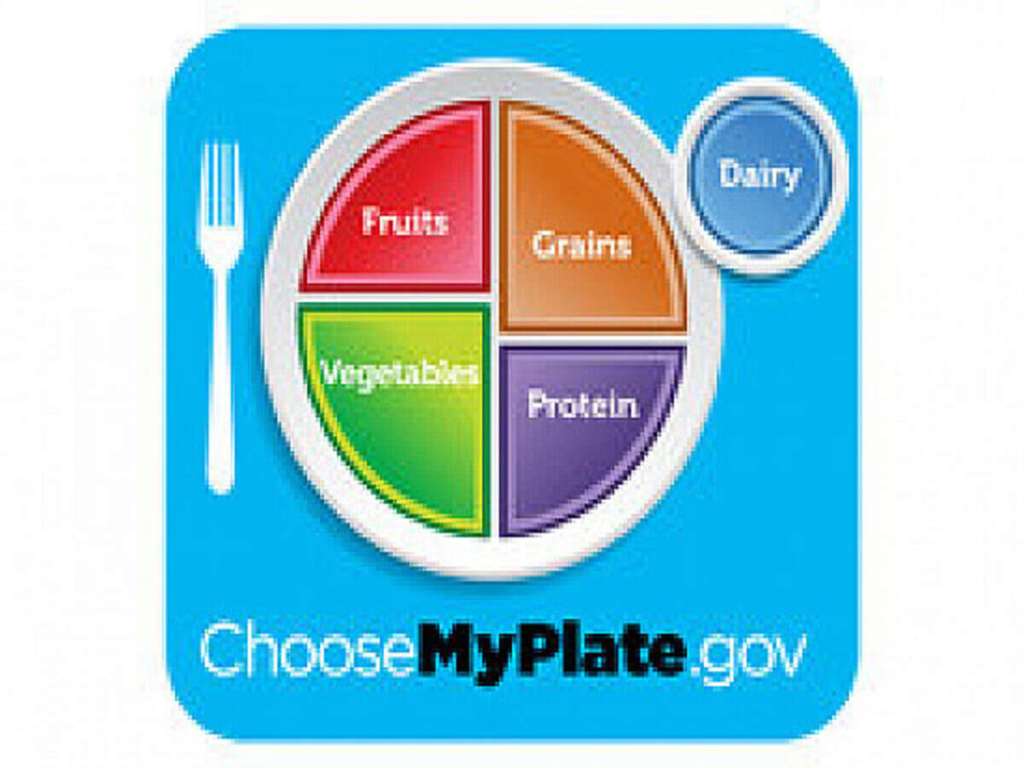

In 2005, the MyPyramid Food Guidance System was introduced and, for the first time, included the message that exercise was a core component of a healthy lifestyle by adding steps with the image of a person. The MyPyramid system included a website that provided more detailed and individualized information. In 2011, after several years of consumer research, the USDA introduced MyPlate to replace MyPyramid. The MyPlate image was thought to be closer to how consumers view food, i.e., sections of a plate divided into the four food groups with dairy on the side. MyPlate has fostered the concept of “make half your plate fruits and vegetables” among consumers. But the release of MyPlate was not without controversy. The food groups included are fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy, and protein. Labeling a group by a nutrient, protein, rather than by foods, had not been done before and raised concerns. The meat and poultry industries feared that people might not understand the options for that category and would assume meat and poultry should not be consumed. The protein category of MyPlate includes meat, poultry, seafood, beans and peas, eggs, processed soy products, and nuts and seeds.

What are the main issues with the food pyramid?

In the 1990s, the Food Pyramid was everywhere. The food guidance system, which was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a nutrition education tool for Americans, was plastered on cereal boxes and bagged bread, in TV commercials, and elementary classrooms.

Not only that, it was published at a time when Americans had a dramatically different understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet, fueled by a combination of supply chain imbalances, outdated science, and good marketing. Back then, cholesterol was the enemy, and saturated fat was taboo. Egg whites were encouraged over egg yolks, margarine over butter, and fat-free over full-fat. But low fat invariably meant high carbohydrate—especially wheat—and America had lots of that.

U.S. health officials reportedly picked the Pyramid over a bowl design because it did a better job communicating moderation and proportions. It also mimicked a popular food Pyramid created in Sweden in the 1970s that recommended healthy foods with a focus on affordability and avoiding fat.

The USDA Food Pyramid was controversial from the beginning. After work went into developing the Pyramid for several years, the brochure for the Pyramid was sent to the printer in early 1991. But then representatives for the National Cattlemen’s Association reportedly saw media coverage that “stigmatized their products”—by putting beef in the same category as fats and dairy. The organization joined other industry groups, such as the National Milk Producers Federation, protesting the Pyramid, and the rollout was postponed.

The Pyramid reportedly spent another year in revisions—at a cost of about $900,000 to taxpayers—and when the updated version was released to the public in 1992, the nutrition experts who developed the guide were surprised by several of the changes. The suggested servings of grains were higher than their original recommendation, and the recommended number of servings of fruits and vegetables had shrunk.

These food-choice changes put the USDA’s own nutritionists at odds with the influential food industry. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has an inherent conflict of interest: its primary mission is to ensure the success of the American agriculture industry, so its nutritional advice is an inevitable compromise of vested interests.

Was the food pyramid wrong?

Even when the Pyramid was being developed, though, nutritionists had long known that some types of fat are essential to health and can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, scientists had found little evidence that a high intake of carbohydrates is beneficial. But that wasn’t the only issue with the Pyramid. Critics had a laundry list of concerns:

- Why were foods categorized the way they were? (Nuts, beans, and red meat were lumped in the protein category, while all fats and sweets were considered the same. Sugar was also considered a carbohydrate, whether it came from fruit or from soda.)

- Why did the Pyramid recommend all Americans eat at least six servings of grains a day?

- Why didn’t the USDA differentiate between the types of fats? (By the early 90s, researchers knew that monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat — both unsaturated — contributed to a healthy diet, while trans-fats were really bad.)

MyPyramid riffed off the original Pyramid while also putting in place a handful of changes. The new design didn’t include any details; instead, it assigned a color to each food category—green for vegetables, orange for grains—and promoted MyPyramid.gov, a website that had dietary recommendations while also suggesting people manage total calories and get physical exercise. It was the first federal food guide to have an interactive online component.

The changes were applauded by some, but by then, there were already concerns that the original Pyramid didn’t do enough to encourage Americans to limit their consumption of refined carbs, and was a driving factor in the growing obesity crisis.

A study in The Journal of Nutrition in 2006 that analyzed dietary habits for about 4,300 adults found that people who followed the MyPyramid recommendations were more likely to get their nutritional needs met than those who adhered to the original Pyramid. However, the researchers also said that following the newer recommendations could still lead to excessive energy intake, a contributing factor to obesity, chronic diseases, and metabolic disorders.

The most sweeping change to America’s food-guide history came in 2011 with the introduction of MyPlate, a totally new design that focuses on a plate with four food groups: vegetables, fruits, protein, and grains. Dairy is represented by a circle placed on the side of the plate, much like a glass of milk. It also recommends physical activity and eating fewer foods with added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.

The easy-to-understand plate design was applauded by both scientists and the food industry, though there are still concerns about some of the recommendations and their purported health benefits, and some researchers have come up with their own food guides.

Are Americans following the dietary guidelines?

More than a decade after Agriculture Department officials ditched the pyramid, few Americans have heard of MyPlate, a dinner plate-shaped logo that emphasizes fruits and vegetables. Only about 25% of adults were aware of MyPlate – and less than 10% had attempted to use the guidance, according to a study released by the National Center for Health Statistics. Those figures for 2017-2020 showed only slight improvement from a similar survey done a few years earlier.

That means that the Obama administration program that costs about $3 million a year hasn’t reached most Americans, even as diet-related diseases such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease have continued to rise.

Main benefits of MyPlate are:

- Simplicity and Clarity: MyPlate offers a straightforward visual guide, making it easy for people of all ages to understand the basics of a balanced diet. The division into four food groups plus a side of dairy simplifies the process of meal planning. It eliminates the need for counting calories or measuring portions meticulously, encouraging more people to adopt healthier eating habits.

- Customizable to Individual Needs: The flexibility of MyPlate allows for adjustments based on individual dietary requirements. Whether you are an athlete needing more protein or someone who is lactose intolerant and requires alternative sources of calcium, MyPlate’s structure supports personalization. This adaptability ensures that diverse nutritional needs and preferences can be met with ease.

- Promotion of Fruits and Vegetables: By designating half the plate to fruits and vegetables, MyPlate emphasizes the importance of these food groups for a healthy diet. This focus helps to increase the intake of essential vitamins, minerals, and fiber. It aligns with numerous studies that highlight the benefits of fruits and vegetables in reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

- Encourages Whole Grains: MyPlate advises making at least half of your grains whole grains, which promotes the consumption of healthier grain options. Whole grains are linked to a lower risk of heart disease, diabetes, and other health issues. This guidance helps individuals make smarter carbohydrate choices.

- Supports Portion Control: Although criticized for not specifying portion sizes, the visual representation inherently encourages portion control by dividing the plate into sections. This method can help people visualize and limit how much they eat without the need for precise measurements, aiding in weight management.

- Educational Tool: MyPlate serves as an excellent educational tool in schools and public health campaigns. Its simplicity makes it accessible to children, helping instill healthy eating habits from a young age. Educators can use it as a base for teaching nutrition basics, fostering a generation that is more aware of dietary balance.

- Incorporates Dairy: Including dairy or a dairy substitute provides a source of calcium and vitamin D, nutrients essential for bone health. This aspect of MyPlate ensures that people remember to include these important nutrients in their daily diet, which might otherwise be overlooked.

- Accessible and Free Resource: MyPlate is available for free online, making it accessible to a wide audience. Its resources, including detailed guidelines and tips for each food group, are readily available to anyone with internet access, removing barriers to nutritional information.

- Reflects Dietary Guidelines: MyPlate is based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, ensuring it reflects current nutritional science and recommendations. This basis in scientific research adds credibility and reliability to the guidance it provides.

- Versatile for Different Diets: Despite its basic structure, MyPlate can be adapted to fit various dietary patterns, including vegetarian and vegan diets. By substituting animal-based proteins and dairy with plant-based alternatives, individuals can still follow MyPlate’s principles while adhering to their dietary restrictions or preferences.

The main criticism of MyPlate includes:

- Lacks Specifics on Portion Sizes: The absence of explicit portion sizes in MyPlate’s visual guide can lead to confusion. Without precise measurements, individuals may struggle to determine the correct amounts of food they should consume, potentially leading to overeating or inadequate nutrition.

- Oversimplifies Complex Nutrition: By focusing on food groups without delving into the nuances of nutrient density or the quality of food within each group, MyPlate may oversimplify nutritional needs. This approach might neglect the importance of selecting whole, unprocessed foods over their refined counterparts.

- Not Tailored to All Dietary Needs: While MyPlate offers a general framework, it might not suit everyone’s specific health conditions or dietary restrictions. People with certain medical conditions, like diabetes or heart disease, may require more tailored dietary advice that takes into account carbohydrate counting or sodium intake.

- Dairy Emphasis May Not Fit All: The inclusion of a dairy section might not align with the dietary habits of lactose intolerant individuals or those following a vegan lifestyle. This emphasis on dairy could inadvertently suggest that it’s indispensable for a healthy diet, overlooking the variety of calcium-rich, non-dairy alternatives available.

- May Not Address Modern Dietary Trends: As dietary trends evolve, MyPlate may not fully encapsulate the nuances of modern diets, such as keto, paleo, or intermittent fasting. These diets focus on specific macronutrient distributions that don’t necessarily fit within the MyPlate framework.

- Potential for Misinterpretation: The simplicity of MyPlate, while a strength, can also be a drawback. Individuals might misinterpret the visual guide as an endorsement of all foods within a group as equal, not recognizing the need for lean proteins over fatty ones or whole fruits over juices.

- Neglects Hydration: MyPlate does not explicitly include guidance on hydration, an essential aspect of overall health. Water intake is crucial for bodily functions, yet the model does not address this, potentially overlooking a key component of nutritional well-being.

- Limited Guidance on Healthy Fats: MyPlate does not have a specific section for fats, which are an important part of a balanced diet. Healthy fats, such as those from avocados, nuts, and seeds, are essential for brain health and energy, but their absence in the model could imply they are of lesser importance.

- Can Be Perceived as Too General: For individuals seeking detailed nutritional guidance, MyPlate may appear too generic. It provides a broad overview rather than detailed advice on how to balance macronutrients or manage specific dietary goals, such as muscle gain or fat loss.

- Does Not Address Processed Foods: While MyPlate promotes a balance of food groups, it does not explicitly discourage the consumption of processed foods. This omission might lead individuals to assume that processed foods can be a significant part of a healthy diet if they fit into the MyPlate categories, potentially undermining nutritional quality.

In conclusion, while MyPlate offers a simplified and visually engaging approach to meal planning that accommodates a broad audience, it is not without its limitations.

The model’s emphasis on balance and flexibility must be weighed against its shortcomings in providing detailed guidance on portion sizes, addressing individual nutritional requirements, and adequately managing fat and sugar intake. As dietary needs vary significantly among individuals, exploring alternatives and considering personalized advice from nutrition professionals is advisable for optimal dietary planning.