Approximately 6% of the total population consumed oatmeal, with an average intake of 238 g/day of cooked oatmeal among consumers. The greatest prevalence of oatmeal consumption was in infants (14.3%) and older female adults (11.1%). Amongst oatmeal consumers, underweight, normal weight, and overweight individuals consumed significantly more oatmeal than obese individuals. Oatmeal was consumed almost exclusively at breakfast and, among consumers, contributed an average of 54.3% of the energy consumed at breakfast across all age groups.

Few breakfast foods are more popular or inviting than oatmeal. With an estimated $5.3 billion market size, people love that the dish is filling, inexpensive, and easy to prepare. Made by heating raw oats with water or milk to make a porridge, oatmeal has a rather bland taste on its own but is frequently spiced or sweetened with toppings like sugar, cinnamon, honey, or fruits like apple slices, blueberries, strawberries, or bananas.

Oatmeal is a well-balanced meal and a good source of folate, copper, iron, zinc, and several B vitamins. It’s also an excellent source of beta-glucan, which can help with heart health, The American Heart Association praises oatmeal for lowering cholesterol and for being a rich source of the mineral manganese – which plays important roles in immune health, blood clotting, and the way blood sugar is metabolized. One of the downsides of eating oatmeal is its aforementioned bland flavor. This causes many people to add large amounts of white or brown sugar to sweeten it. The daily value limit of added sugars, as recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is only 50 grams -about 12 teaspoons. It’s not uncommon for people to put a quarter of that amount on a single serving of oatmeal.

How it all started

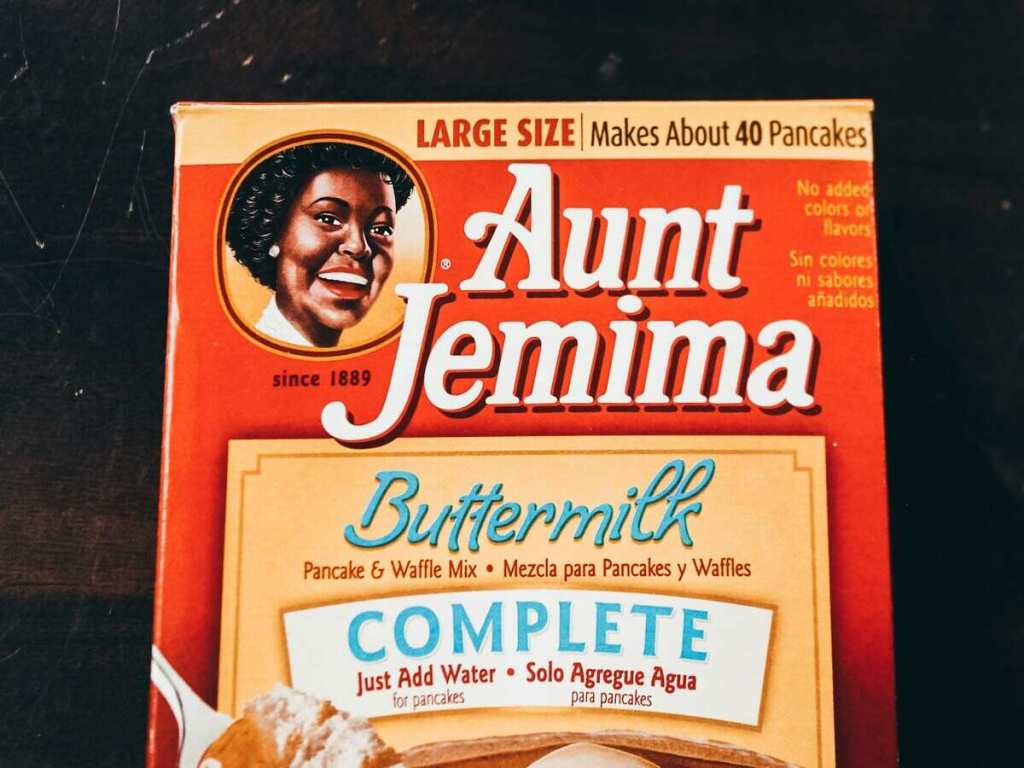

In 1879, the Imperial Mill was built at 16th and Dearborn Streets in Chicago by a group of investors that included John and Robert Stuart. At the end of the 1880s, this oat mill and several other leading mills around the Midwest became part of the American Cereal Co., a grain-milling giant that had its headquarters in Chicago. In 1901, American Cereal became the Quaker Oats Co. (The “Quaker” brand name came from an Ohio mill owned by Henry P. Crowell.) By 1907, Quaker’s annual sales of oatmeal, flour, and feed amounted to $20 million. In 1909, the company used new machines to produce its “Puffed Rice” and “Puffed Wheat” ready-to-eat cereals, which proved popular. Annual sales in 1918 exceeded $120 million. In 1925, the company bought the “Aunt Jemima” mills of St. Joseph, Missouri. By that time, Quaker had begun to use oat hulls to produce the chemical furfural, which was soon used by industry to manufacture nylon and synthetic rubber. The company also became a leading maker of pet foods. In 1942, Quaker purchased Ken-L-Ration Dog Foods of Rockford, Illinois.

By the middle of the 1960s, annual sales approached $500 million, and the company employed about 12,000 people nationwide (only a few hundred of these worked in the Chicago area). The company proceeded to introduce new lines of ready-to-eat breakfast cereals, including its popular “Life” and “Cap’n Crunch” brands, as well as Quaker instant oatmeal. By the middle of the 1970s, when the company employed about 1,800 people in the Chicago area, annual sales were about $1.5 billion. Over the last decades of the century, Quakers continued to make cereals, but its greatest success and greatest failure came with beverages. Its “Gatorade” sports drink brand became an immensely popular and profitable product and helped push Quaker’s global workforce up to 32,000 by 1989. The company suffered in 1994, however, after paying $1.7 billion to acquire the “Snapple” drink brand, which it dumped in 1997 at a huge loss. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, when Quaker grossed nearly $5 billion in annual sales and had about 1,200 workers in the Chicago area and another 10,000 worldwide, the company was acquired by PepsiCo Inc. of New York.

The Quaker Mill Company, founded in 1877, was so named because one of the founders read about the Religious Society of Friends, widely known as Quakers, and decided the values they represented—integrity, honesty, and purity—would be good ones to associate with their company and products.

The icon of the jolly-looking Quaker gentleman was drawn based on an old woodcut image of William Penn, founder of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the best-known Quaker in the U.S. Over the years, the icon evolved into a colorful illustration of a substantial-looking 17th-century white man, still sporting a “Quaker” hat and the white wig of that period; and in 1969, the image was redrawn as a modern logo by Saul Bass of movie title and corporate logo fame. In the mid-1960s, they even used the brand tagline, “Nothing is better for thee than me.” The Quaker Man was supposedly the first trademarked breakfast cereal logo.

The ‘Quaker man’ is not an actual person. His image is that of a man dressed in Quaker garb, chosen because the Quaker faith projected the values of honesty, integrity, purity, and strength

Quaker Oats Scandals

Racism

Quaker Oats created the Aunt Jemima brand in 1885, twenty years after the abolition of slavery. Disgusted with the emancipation of slaves, Quaker Oats CEO, Henry Parsons Crowell, decided to symbolically keep slavery alive by kidnapping a local fat black woman and forcing her to play the Aunt Jemima character, and be the mascot for the brand. When that woman died of diabetes in 1921, Quaker Oats decided that it was in their best interest to keep zero of the African American population on staff.

Quaker Oats announced they would be removing Aunt Jemima from all of their syrups and pancake mixes. The company made the brash decision based on Aunt Jemima’s origins being, “based on a racial stereotype”. While Quaker Oats stands firm with this being their genuine intention, I can’t help but think they’ve used this opportunity as a veil to mask the company’s real reason. To fire their only black employee.

Their first racist cereal, Life, was created in a Quaker Oats board room in 1972. Originally, the cereal’s name was “Life in Prison”, named after what they wish all black criminals were charged with. They even went as far as having the actual cereal look like bars in a jail cell. While the cereal was approved by the FDA, the original mascot “Uncle Tom” was not.

Radioactive oats

The Fernald State School, originally called The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded, housed mentally disabled children along with those who had been abandoned by their parents. Conditions at the school were often brutal; staff deprived boys of meals, forced them to do manual labor, and abused them. The boys didn’t find out the whole story about their contaminated cereal for another four decades. During a stretch between the late 1940s and early 1950s, Robert Harris, a professor of nutrition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led three different experiments involving 74 Fernald boys, aged 10 to 17. As part of the study, the boys were fed oatmeal and milk laced with radioactive iron and calcium; in another experiment, scientists directly injected the boys with radioactive calcium.

The Fernald students’ experiment was just one among dozens of radiation experiments approved by the Atomic Energy Commission. Between 1945 and 1962, more than 210,000 civilians and GIs were exposed to radiation, often without knowing it. What seems unthinkable in today’s era of ethics review boards and informed consent was standard procedure at the dawn of the Atomic Age.

How did a seemingly innocuous breakfast food get tied up with Atomic Age research? At the time, scientists were eager to conduct experiments concerning human health, and the booming breakfast cereal industry meant there was big money to be made or lost. As a result, brands like Quaker wanted science on their side. They’d been locked in competition with another hot breakfast cereal—Cream of Wheat, made with farina—since the early 1900s. And both of the hot cereal companies had to contend with the rise of sugary dry cereals, served with cold milk and a heaping portion of advertising.

To make matters worse for Quaker, a series of studies suggested high levels of phytate (a naturally occurring cyclic acid) in plant-based grains—like oats—might inhibit the absorption of iron, whereas farina (Cream of Wheat) didn’t seem to have the same effect. The market for cereal products was booming—in the post-WWII years, Quaker’s sales grew to $277 million. Nutrition was high in the minds of buyers of the era, especially since the Department of Agriculture produced its first dietary guidelines in 1943, including oatmeal as an ideal whole grain. Television advertisements from the 1950s highlighted Quaker Oats’ nutritional content as a selling point.

A hearing before the Senate’s Committee on Labor and Human Resources was called in January 1994 to investigate the Fernald experiments. During the session, Senator Edward Kennedy, the committee chair, asked why researchers hadn’t conducted the experiment on MIT students or children at private schools. At the Senate hearing, David Litster of MIT said the experiment involving oatmeal only exposed the boys to 170 to 330 milligrams of radiation, roughly the equivalent of receiving 30 consecutive chest x-rays.

A 1994 Massachusetts state panel concluded none of the students suffered significant health impacts, and radioactive tracers continue to be used in medicine.

But the real issues weren’t simply a matter of future health risk: the boys, who were especially vulnerable without parents and guardians looking out for their best interests in the state school, were used for experiments without their consent.

When the case went to court, 30 former Fernald students filed suit against MIT and Quaker Oats. In 1995, President Clinton apologized to the Fernald students, since the Atomic Energy Commission had indirectly sponsored the study with a contract to the radioactivity center at MIT. A settlement for $1.85 million was reached in January 1998. Even before this particular case, regulations like the National Research Act of 1974 had been enacted to protect Americans from unethical experiments.

Pesticides

In recent years, health-conscious consumers have become increasingly concerned about the safety and quality of the food they consume. One such alarming issue that has garnered attention is the presence of pesticides in commonly consumed food products. The Quaker Oats pesticide lawsuit is a stark reminder of the potential risks lurking in our breakfast bowls.

The lawsuit stems from allegations that Quaker Oats, a well-known brand owned by PepsiCo, has been producing oat-based products containing traces of chlormequat, a widely used herbicide. Exposure to chlormequat can disturb fetal growth, sperm mobility, puberty development, alter metabolism, and harm the nervous system.

Earlier, Quaker Oats had faced lawsuits on the presence of another pesticide, glyphosate, an active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup. Glyphosate has been classified as a probable carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), raising serious health concerns.

Consumers who have filed lawsuits against Quaker Oats argue that the company failed to adequately disclose the presence of chlormequat in its products, misleading consumers into believing that they were purchasing a safe and wholesome breakfast option. The controversy has sparked debates over food safety regulations, corporate responsibility, and the need for greater transparency in the food industry.

The implications of the Quaker Oats pesticide lawsuit extend beyond just one brand or product. It underscores broader concerns about the prevalence of pesticides in our food supply chain and the potential health risks associated with long-term exposure to these chemicals. While chlormequat is commonly used in agriculture to control weeds, its presence in food products raises questions about its impact on human health, particularly when ingested regularly over time.

The lawsuit has also reignited discussions about the regulation of pesticides and the need for more stringent testing and monitoring protocols to ensure the safety of food products. Critics argue that current regulations may not adequately protect consumers from exposure to harmful pesticides, highlighting the need for reforms to safeguard public health.

Furthermore, the Quaker Oats pesticide lawsuit serves as a wake-up call for consumers to become more vigilant about the products they purchase and consume. It underscores the importance of reading labels, conducting research, and demanding transparency from food manufacturers. In an age where consumers have access to vast amounts of information, empowering one with knowledge about the products they buy is crucial in making informed choices for their health and well-being.

As the Quaker Oats pesticide lawsuit unfolds, it serves as a reminder that the food we eat is not always as safe as we may assume. It underscores the importance of holding food manufacturers accountable for the products they produce and the need for greater oversight of the food industry. Ultimately, it is incumbent upon both companies and regulatory authorities to prioritize consumer safety and ensure that the food we consume is free from harmful contaminants.

Salmonella

Quaker Oats was once named the top brand on social media, which is one of the many reasons it’s so popular. However, Quaker Oats fans will have to refrain from eating some of its products in the wake of a recent recall. Though it isn’t as bad as the Quaker Oats scandal you’ve likely never heard of, according to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Quaker Oats has issued a recall of various products containing salmonella, a form of bacteria that can hospitalize or have a lethal effect on kids, vulnerable seniors, and those who are immunocompromised. Unfortunately, the list of products that are being recalled is very long. It includes 25 of Quaker Oats’ popular granola bar snacks, including Quaker Big Chewy Bars in chocolate chip, peanut butter chocolate chip, and Quaker Chewy Bars Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough.

Granola bars that come in 10 of Quaker Oats’ snack boxes are being recalled as well, including Quaker Chocolatey Favorites Snack Mix, Quaker On The Go Snack Mix, and Frito-Lay and Snacks Variety Pack With Quaker Chewy. Eight of Quaker Oats’ popular cereal products have also been listed for possibly being tainted with salmonella, including Quaker Puffed Granola varieties and Quaker Simply Granola Oats, Honey & Almonds Cereal.

Per the Mayo Clinic, salmonella impacts the intestines, and if you are infected with it, you may experience symptoms between six hours and six days after you’ve been infected. Some of those symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and blood in the stool. There is a possibility that you can be asymptomatic while infected with salmonella. If you experience symptoms, you should know that symptoms typically last from two to seven days. Infected people usually recuperate after several days without medical attention.

What is the situation with Quaker oats now?

The Quaker Oats Company issued a recall in late 2023 and added more products to its recall list in 2024 due to a risk of contamination with salmonella. There are more than 100 recalled products that the Quaker Oats Company is encouraging consumers to avoid. Salmonella is a type of bacteria that can be deadly when ingested by certain at-risk groups. Products affected by the Quaker recall include granola cereals and bars, Oatmeal Squares cereal, Cap’N Crunch cereals and bars, snack boxes, and more.

The company first announced the recall in mid-December 2023, along with the roughly 90 products affected, and in mid-January 2024, the company added over 40 products more to the Quaker recall list. There is currently a recall affecting several types of Quaker Oats Company products, but the recall does not include the product Quaker Oats itself or Quaker Instant Oats. The recall was first announced on Dec. 15, 2023, and it affected primarily namely bars and cereals. The company said affected products may have been contaminated with salmonella, a type of bacteria that normally lives in human and animal intestines and is shed through stool. In certain groups, a salmonella infection can be deadly.

On Jan. 11, 2024, the FDA posted that over 40 more products were being added to the recall list. These include additional varieties of Chewy granola bars and cereals, Cap’N Crunch cereals and bars, Quaker oatmeal squares, Gatorade protein bars, and Munchies snack mix. The entire country is affected by the recall with the products being sold in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Guam and Saipan, a U.S. Commonwealth.

One of Vermilion County’s largest employers is closing down and laying off its workforce. Production has ceased at the Quaker Oats plant in Danville, leaving approximately 510 employees without work. Chicago-based Quaker Oats, a unit of Pepsico since 2001, opened the plant in 1969. In recent years, the Danville plant manufactured Quaker Oats granola bars, but it also made cereal and pancake mix. In a statement, Quaker Oats said that after a granola bar recall in December, they decided that it was best to consolidate manufacturing of the product in a newer facility.

When PepsiCo (PEP) acquired Quaker Oats in 2000 for around $14 billion in stock and debt, the Gatorade sports-drink business was the real prize.

After the deal closed, Pepsi considered selling the non-beverage portion of the Quaker unit. According to one industry banker, the potential sale was complicated by the need to de-lever the Quaker brand related to the parts Pepsi did not want — namely the cereal business — from the parts it wanted to keep, such as the granola-bar unit. That’s because the Quaker brand name was used across a wide range of products.

While the brand is battling with even more pesticide-related troubles and hopefully no more future recalls it seems that the public has lost its trust in the company. Most of the consumers are turning to store-bought brands and more expensive organic ones that have not been connected to any recent recalls and scandals.